Slab Rebalancing - How Does It Work?

Goal

This doc will explain in depth how slab rebalancing works in RAM cache. We will cover the following aspects:

- Why do we need to rebalance?

- How do we pick a slab to release?

- How do we maintain strict LRU ordering during a slab release?

- How do we handle chained items when they're spread across multiple slabs?

- What is the synchronization mechanism during a slab release?

High Level Overview

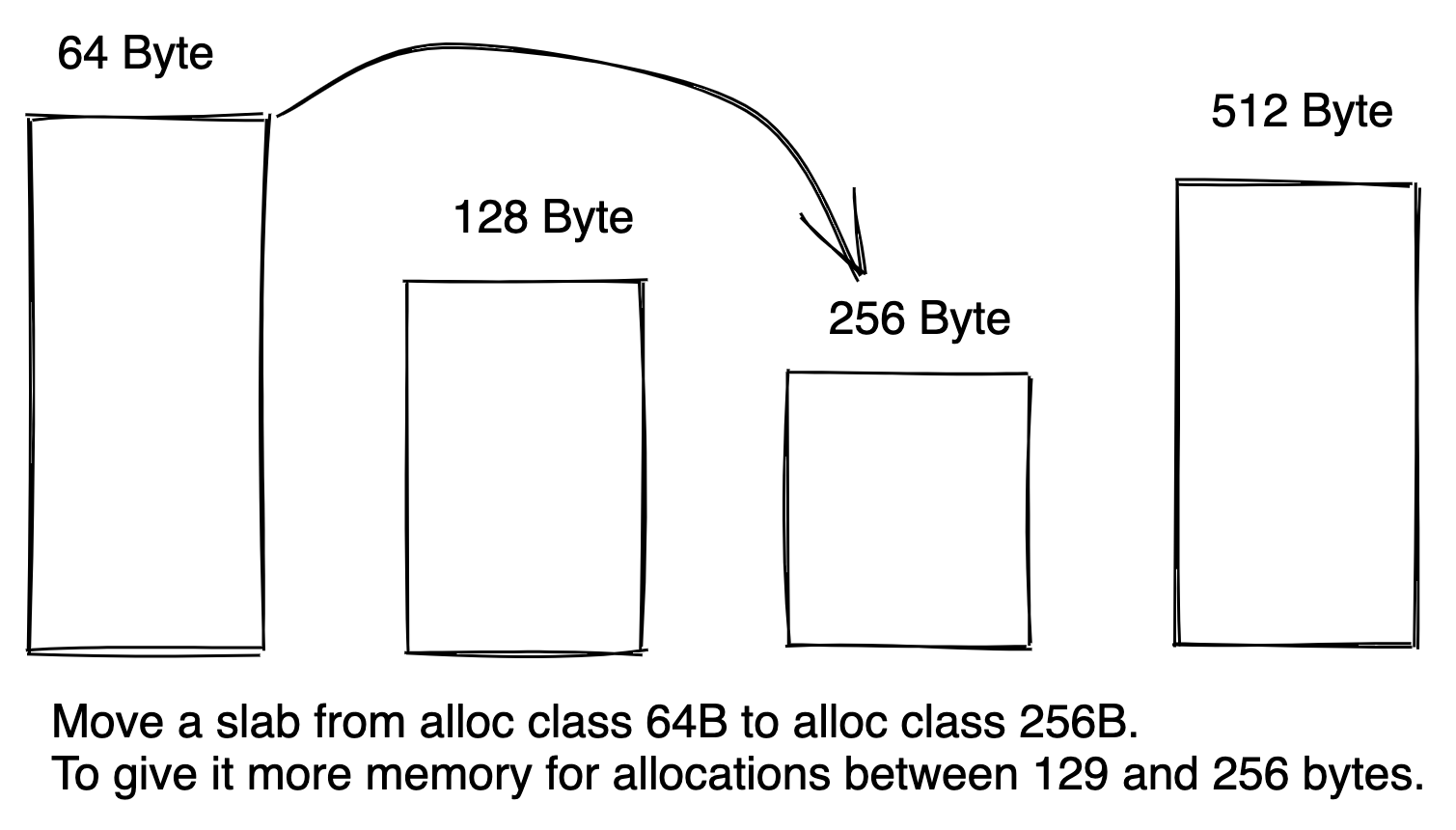

Slab rebalancing is the act of moving one slab from one allocation class to another. CacheLib allocates memory from a slab allocator in which we assign one allocation class (also known as slab class) for each size granularity. When cache becomes full, for a particular allocation size user requests, CacheLib evicts an item of the same size granularity and returns the recycled memory back to the user. Due to this design, it is important to balance the numbers of slabs in each allocation class. Issues such as allocation failures or unexpected imbalance between eviction ages of different sized objects can happen when user requests a lot of items of a particular size, but the allocation class for that size has very few numbers of slabs.

Slab rebalancing is the act of moving one slab from one allocation class to another. CacheLib allocates memory from a slab allocator in which we assign one allocation class (also known as slab class) for each size granularity. When cache becomes full, for a particular allocation size user requests, CacheLib evicts an item of the same size granularity and returns the recycled memory back to the user. Due to this design, it is important to balance the numbers of slabs in each allocation class. Issues such as allocation failures or unexpected imbalance between eviction ages of different sized objects can happen when user requests a lot of items of a particular size, but the allocation class for that size has very few numbers of slabs.

To rebalance, we first pick a slab from an allocation class, and then evict or move each item in the slab. After that, we can free this slab, and give it to another allocation class. Slab rebalancing is an intra-pool operation. However, moving slabs between different memory pool (due to pool resizing) follows the same logical operations. Now, let's walk through each step in slab rebalancing in details below.

Details

1. Why do we need to rebalance

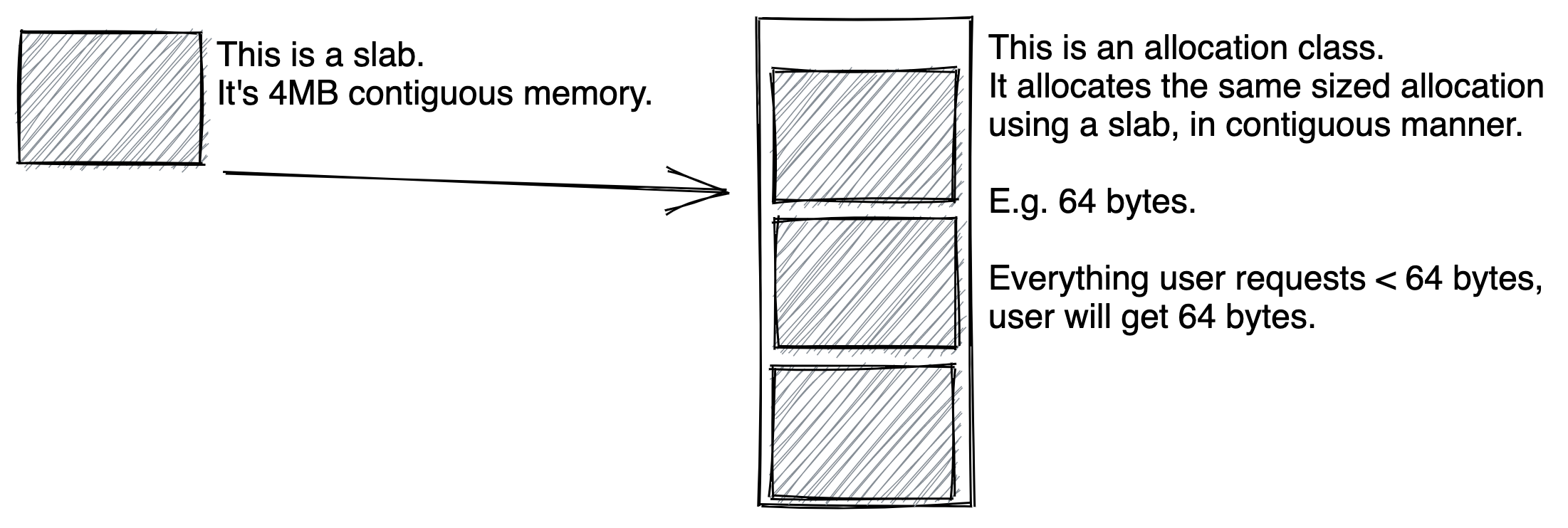

CacheLib allocates memory from a slab allocator in which we assign one allocation class (also known as slab class) for each size granularity. In the slab allocator design, memory is partitioned into a number of slabs. For CacheLib, each slab is 4MB. Each allocation class is responsible for allocating for a particular size granularity. In the beginning, none of the allocation classes have any memory. When an allocation request comes from the user, we will take one slab from the free slabs, and give it to an allocation class. Once the allocation class has at least one slab, it will start allocating contiguously at the size granularity. Once the allocation class has no more free slab left, it can ask for another from the free slabs. When free slabs run out, it will start evicting items to make space for a new allocation. Note that the evictions can happen within just one allocation class because each is paired with a LRU (or 2Q, or another eviction policy).

CacheLib allocates memory from a slab allocator in which we assign one allocation class (also known as slab class) for each size granularity. In the slab allocator design, memory is partitioned into a number of slabs. For CacheLib, each slab is 4MB. Each allocation class is responsible for allocating for a particular size granularity. In the beginning, none of the allocation classes have any memory. When an allocation request comes from the user, we will take one slab from the free slabs, and give it to an allocation class. Once the allocation class has at least one slab, it will start allocating contiguously at the size granularity. Once the allocation class has no more free slab left, it can ask for another from the free slabs. When free slabs run out, it will start evicting items to make space for a new allocation. Note that the evictions can happen within just one allocation class because each is paired with a LRU (or 2Q, or another eviction policy).

This design means that the number of slabs in each allocation class depends on the allocation request pattern before a cache is warmed up. In a hypothetical scenario, a use-case may request only 100-byte objects during the day and only 1000-byte objects during the night. This means with a naive slab allocator design, if we start up a new cache during the day, by the time night arrives, we do not have any available memory for 1000-byte objects, and are unable to evict anything because all items in the cache are 100-byte.

For obvious reason, this is bad. The way to solve this issue is via slab rebalancing. We will move a slab from 100-byte allocation class to 1000-byte allocation class, so it has memory to evict. Next, let's examine how we can pick a slab.

2. How do we pick a slab

There are several objectives for moving slabs around.

- Minimize allocation failures.

- Ensure fairness in how long an object might stick around in cache.

- Optimize the cache composition to drive the highest objectwise-hitrate.

Note that 2 & 3 are often times opposite goals. A cache may get a lot more "get" requests for objects within a certain size granularity, if we move as many slabs to that size to maximize the "hits/byte", we will maximize objectwise hit rate, but at the expense of the cache retention time fairness for objects of a different size.

CacheLib offers four different rebalancing policies:

- RebalanceStrategy{} - Default policy. This addresses 1. It will only be triggered when we detect allocation failures.

- LruTailAgeStrategy{} - This addresses 1 & 2. It moves slab from AC with the highest "eviction age" to one with the lowest.

- HitsPerSlabStrategy{} - This addresses 1 & 3. It moves slab from AC with the lowest "hits per slab" to one with the highest. It assumes a linear relationship between hits and number of slabs.

- MarginalHitsStrategy{} - This addresses 1 & 3. It has the same goal as HitsPerSlabStrategy, but assumes a non-linear relationship. It tries to approximate the marginal return by using only the hits of the "last slab" of an AC to determine the increase in hits if it were to get another slab.

Once we have picked an allocation class as a victim for giving up a slab, we will pick a slab at random (we do this by taking a slab from the end of the allocated slab list in an AC).

3. How do we maintain strict LRU ordering

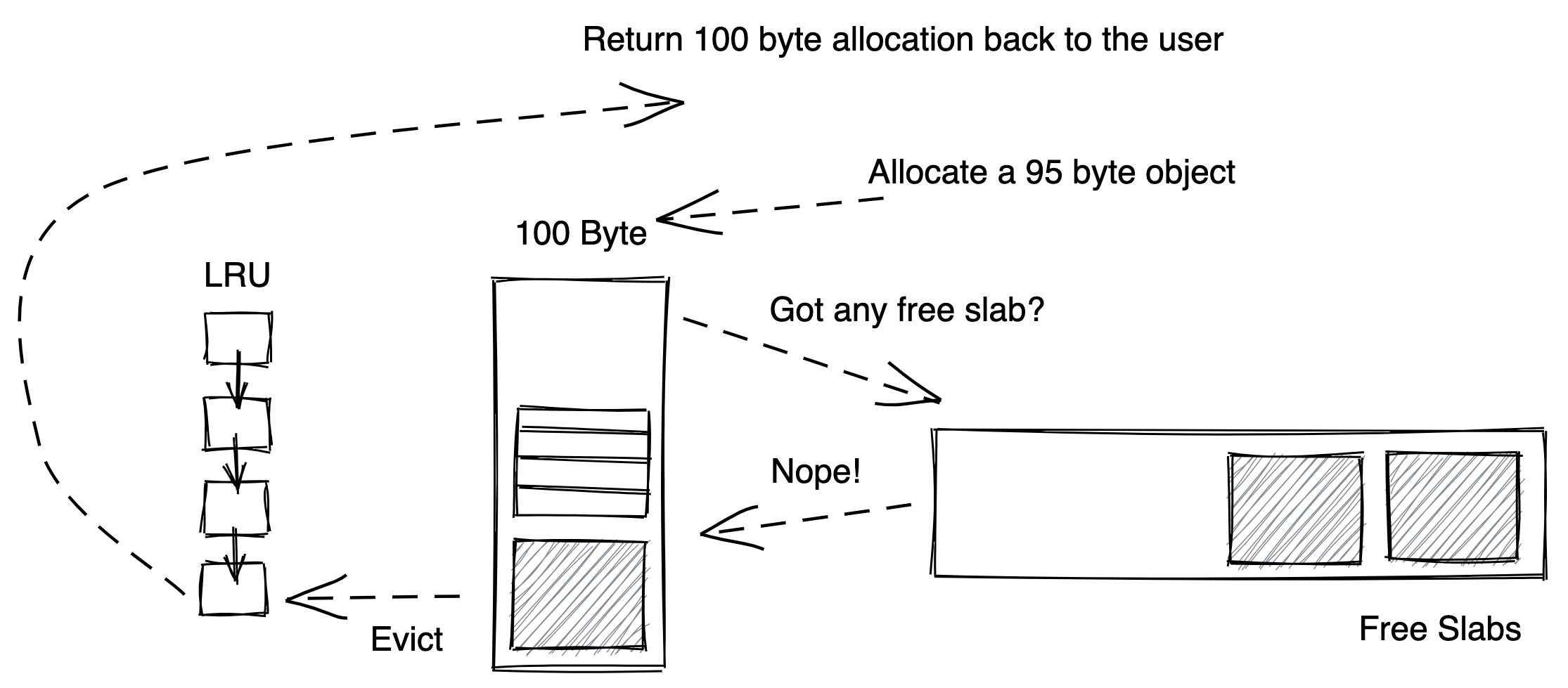

Once we have picked a slab, we have to release it. CacheLib follows the following algorithm for slab release:

- Mark the slab as "in slab release"

- Filter out all "freed" allocations in this slab

- Walk through each "active" allocation

- (two different algorithms)

- Evict this allocation

- Maintain strict LRU ordering via memcpy (or user callback) the content of an item to another item by evicting from the tail of LRU in the same allocation class. (Note: if there're any free items in the AC, we will first allocate from the free list)

- Once all done, free the slab

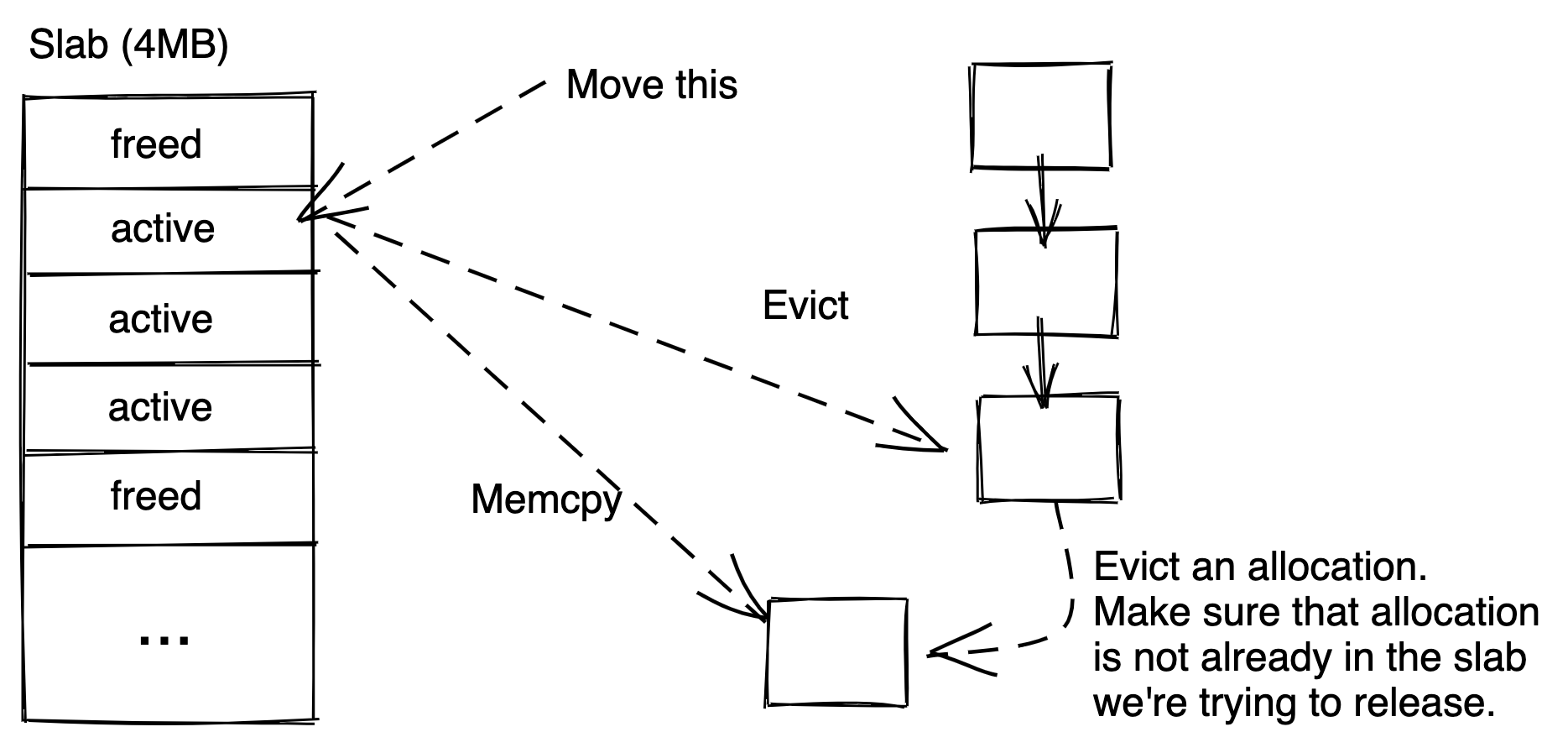

Note that 4(a) is self-explanatory; we're just evicting everything still active in this slab until the slab is devoid of any allocations still being used by the user. 4(b) is the more involved one as the goal here is to maintain strict lru ordering. The way it is done is as follows. User is responsible for choosing which algorithm to use for step 4. 4(b) is enabled if user specifies a moving callback (memcpy or some custom callback logic).

When we evict from the tail of the LRU to make room for the item we're "moving". We make sure we only evict an item from another slab. Note we may actually evict an item that is in the same slab currently being released. This is fine as it is both rare and also that later on when we get to that item, we will move it again to a new allocation. The overall "move"s we complete are still bound by the number of active allocations in the slab.

4. How do we handle chained items

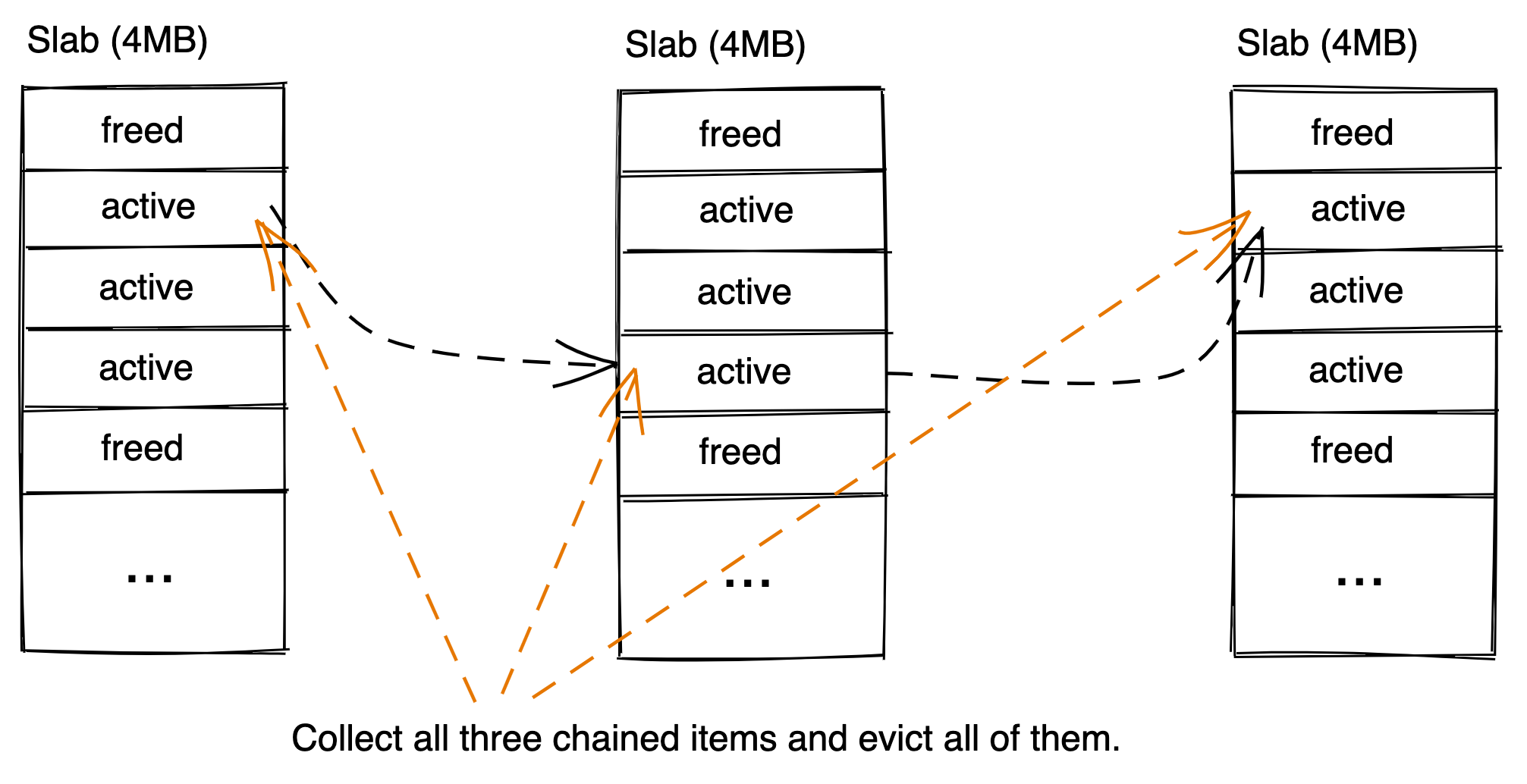

Chained items enable user to tie several allocations together to form a single lifetime. Conceptually, they're a linked list of allocations. User first creates a parent item, which has a key, and is the head of a chain. Then user will create children items, which do not have a key, and append them to the parent one by one. Each allocation in the list can be of a different size. On eviction, we evict the entire chain. This poses a challenge to slab rebalancing. We must ensure when we choose to evict allocations during slab release, we must also evict any chained items to the allocations. Similarly, when we choose to "move" allocations during slab release, we must re-link any moved allocation to their chained items. Eviction for Slab Release

- Pick an allocation to evict

- Check if this item is a parent or a child

- If parent, evict it directly which will also free the children

- If child, find the parent and evict the parent

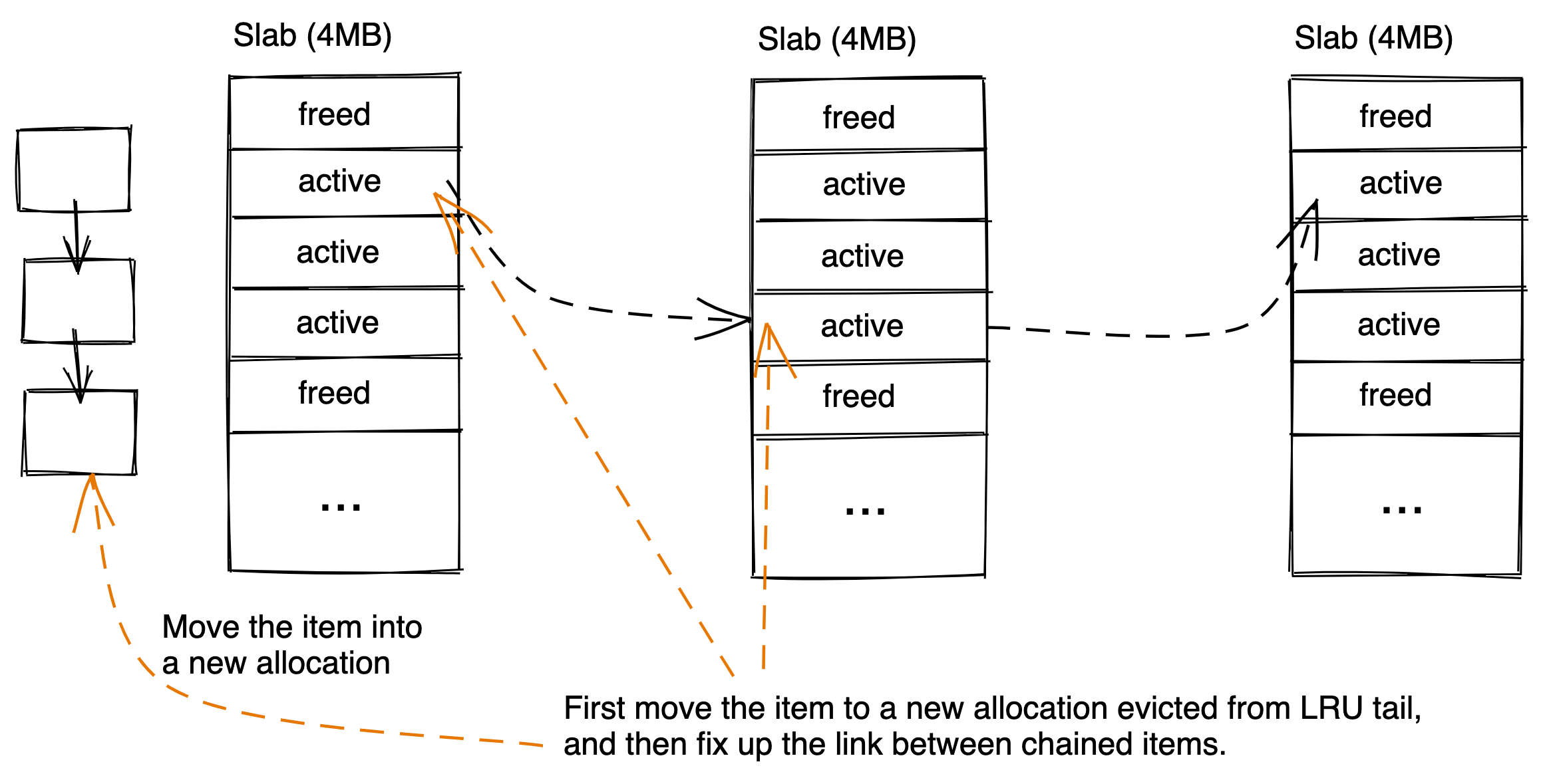

Moving for Slab Release

- Pick an allocation to move

- Check if this item is a parent or a child

- If parent, move it into a new allocation, and relink each of its children to it

- If child, move it into a new allocation, and fix up the link from the previous child to the moved child

5. How do we synchronize

We synchronize all operations via atomic flags in each item's header, and the use of eviction locks and chained item locks (if involving chained items). The goal of synchronization is to ensure the following:

- We're the only thread that can evict an item (or a chain of items).

- We're the only thread that can mutate the content of an item (or a chain of items).

During slab release, when we pick an allocation, we mark a bit in its header denoting that it is currently being operated on for slab release. This bit will prevent any other thread from evicting this item. Afterwards, if we're freeing this allocation via a regular eviction (4(a) algorithm in section 3), we hold onto the eviction lock for its allocation class (the current allocation class), and also the eviction and chained item lock for its parent (if available, and can be of a different allocation class). This ensures the slab release thread is the only one that can evict this item and its chain if available.

Alternatively, if we're moving this allocation (4(b) algorithm in section 4), we grab eviction lock and chained items similarly as above. But instead of evicting, we will grab an additional (and optional) user-level synchronization primitive (we call it movingSync). This primitive is supplied by our user and it is usually a read-write lock our users use to guard mutation into item content in their code. For obvious reason, we don't need this for immutable workloads. Once we have the locks, we allocate a new item, call user callback to "move" the old item into the new item, and then fix up any links if involving chained items. Finally, we atomically swap the entry in the hash table so the new, "moved" item becomes visible to the user.

Finally, we will not "recycle"/"free"/"evict" an allocation in the slab until the refcount on the allocation has dropped to 0. This is to ensure that user who has looked up an item in the slab release before we removed it from the hash table can still use it safely. It also means in the case of any slowdown in user processing path involving an item in a slab release can slow down the slab release. This is an accepted design tradeoff, as slab release happens in the background and is not latency sensitive.